There is no first strike in karate

空手に先手なし

This is the second in a series of posts to examine Shotokan’s niju kun, Gichin Funakoshi’s list of 20 guiding principles for karate.

The second principle is:

空手に先手なし

In Romaji:

Karate ni sente nashi.

In English, I think the best translation is:

Karate doesn’t initiate violence.

This precept is most commonly translated as “There is no first attack in karate”, but that doesn’t really make sense does it? Does Funakoshi really expect you to wait for the other guy to take a swing before defending yourself? Likewise, if neither side were allowed to attack first, wouldn’t sparring matches be really uneventful and boring?

Two questions come to mind when trying to interpret rules and admonitions from the past:

- What did the authors mean mean when they wrote it?

- Is it still relevant today?

Author’s Intent

The best way to know an author’s intent is to look at his other writings on the topic, and Funakoshi makes his true feelings clear in his master text “Karate-do Kyohan.” There, he encourages taking every avenue to avoid confrontation, from situational awareness, to crying for help, and even fleeing the scene.

But, then Funakoshi goes on to say …

When there are no avenues of escape, or one is caught even before any attempt to escape can be made, then for the first time the use of self-defense techniques should be considered. Even at times like these, do not show any intention of attacking, but first let the attacker become careless. At that time attack him, concentrating one’s whole strength in one blow to a vital point, and in the moment of surprise, escape and seek shelter or help.

In his own words, Funakoshi is saying it’s okay to strike first if you’re convinced a confrontation is unavoidable. But if that’s true, what does “karate ni sente nashi” really mean?

Fortunately, plenty of Funakoshi’s contemporaries also have recorded thoughts on the matter:

Genwa Nakasone

Genwa Nakasone, an author and politician who was instrumental in helping spread karate to mainland Japan, wrote an interpretation of Funakoshi’s 20 precepts, which Funakoshi endorsed. In his interpretation, Nakasone says this precept is derived from the principle of bushido that says one should never draw one’s sword easily and, since karate treats the hands and feet as swords, the same principle applies to karate.

While this isn’t a direct admonition against striking first, I think the fact that Funakoshi endorsed this interpretation, when he must have known it could easily be interpreted that way, speaks volumes.

Kenwa Mabuni

Kenwa Mabuni, founder of Shito Ryu, wrote specifically to address what he saw as two mistaken interpretations of this precept, saying:

- The people who believe that striking first is necessary to ensure victory, and that a passive attitude like “karate ni sente nashi” is inconsistent with budo, forget that the “bu” (武) in “budo” is composed of the characters “戈”, meaning “spear”, and “止”, meaning “stop.” (i.e. Budo seeks to prevent violence.)

But on the other hand …

- The people who think that “karate ni sente nashi” should be interpreted literally, as an admonition against preemptive strikes, forget that, once threatened with harm, one should preempt the enemy’s use of violence and that “this, in no way, goes against the concept of ‘sente nashi.’”

So to Manbuni, you mustn’t always strike first, but striking first is okay when it’s absolutely necessary.

Choki Motobu

Choki Motobu, perhaps the most “streetwise” of the old masters, is known to have encouraged striking first, when justified. To him, “karate ni sente nashi” meant you should not harm others without reason but, once conflict became unavoidable, striking first was not only permitted but necessary.

Modern Interpretation

It’s one thing to understand what four guys living 100 years ago, on an island on the other side of the planet, thought about preemptive striking in self defense, but what does that have to do with me, living here, right now?

Regardless of when, where, or why a thing occurs, justification hinges on two questions:

- Is it legally permitted, and

- Is it morally correct?

The Law

I’m not an attorney, and I’m certainly not an expert in self-defense law in your jurisdiction, but most places I’ve lived have had similar requirements for a self-defense claim: You must reasonably believe there’s an imminent threat of unlawful force.

| Scenario | Justified? |

|---|---|

| Your four-year old threatens you with an orange lollypop. | Probably not “reasonable.” |

| Somebody threatens to kick your butt over the phone. | Probably not “imminent.” |

| You bonk your head on a 2x4 in somebody’s cart while coming around a corner at Home Depot. | Probably not “unlawful.” |

| Some dude comes running right at you in a parking lot, threating to kill you. | Probably justified. |

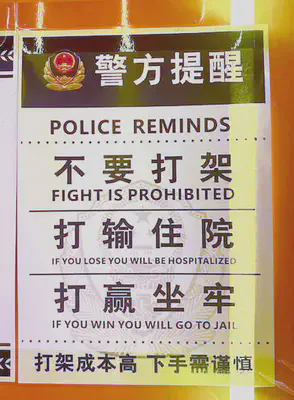

Of course, the burden of proof for a self-defense claim is generally on you. So it’s always best to avoid the confrontation. I often tell students that nobody really wins a fight and the people who think they won are usually thinking it from the back of an ambulance or police car.

Your Conscience

Just because something isn’t illegal doesn’t make it the right thing to do. Only you can answer that, and the slope can get pretty slippery if you’re not careful.

In my opinion, Funakoshi’s sentiments from Karate-do Kyohan are on point.

I will take every opportunity to avoid a confrontation. I’ll avoid dangerous places, I’ll act with courtesy, and I’ll even apologize when I don’t think I’m wrong if I think that will deescalate the situation. But if violence comes looking for me, and gives me no peaceful way out, it needs to know that I can (and will) respond in kind.

This isn’t just a selfish sense of self-preservation. I have people (and dogs) who depend on me. Allowing myself to be injured and allowing those who depend on me to be disadvantaged by my injury, or absence, isn’t something I’m willing to permit. (i.e. I choose my own health and welfare, and that of my family, over that of some creep who’s decided to attack me.)